VD 104: Lessons from 2025

Before we start with the newsletter, I would like to wish everyone a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, and of course good health, much love, happiness, and a great return for 2026.

In This Issue:

Lessons from 2025

Market Overview: Where Do We Stand Today?

Stock in Focus: Scottish Mortgage Trust

The Rationality Test: Lotus Bakeries

What I’ve Been Reading Lately

News from Our Companies

Doubler Portfolio Update

Vacation

Lessons from 2025

The year is already coming to an end—a perfect moment to look back in this final issue on the past year and the lessons I’ve drawn from it.

Investor vs. publisher

In a sense, it’s a continuation of what I learned in 2024, but 2025 proved even more that I am an investor at heart. I find the most satisfaction in reading about companies and, when things go well, conducting in-depth analyses.

I also enjoy writing very much, but I simply don’t get around to the sales side of the magazine enough. In that respect, I actually fit better with a publisher than as a solo entrepreneur.

Nevertheless, I want to thank all readers heartily for your loyalty. The fact that you remain customers for so long motivates me enormously to keep providing you with as much value as possible, even if I’ve had to lower the frequency of the magazine to do so. I hope you’ve already noticed in recent issues that ‘less’ is indeed ‘more’ in this case.

The goal is profit

At the beginning of the year, it briefly looked like it would be ‘our year.’ While stock markets in the United States fell, our portfolio actually did well. Over time, however, the market became immune to Trump, and we continued on the same footing as in 2024.

The goal of investing isn’t simply achieving a good return in itself, but a good return in relation to the risk you take. You must never lose sight of that when comparing results with others.

In the past year, I took little risk and always kept a substantial cash position on hand. Of course, the return could have been higher by holding less cash, but I’m at peace with that; I’d do it again. Doubling your initial investment in five years doesn’t have to happen linearly at 14.5% per year. It can just as easily happen through a series like -2.3%, +8%, +40%, +4%, and +31%. You can rearrange those figures however you like; the end result remains the same.

In the past, the path was also bumpy, as I described in my book (in Dutch). Sometimes the price moves sideways for years, only to suddenly shoot up. Just think of the Great Financial Crisis: first a 38% drop from the peak in just a few months, followed by a doubling within three years of that peak.

What the future brings always remains uncertain. At certain moments, however, there is clear optimism, and that’s why I am satisfied with a solid cash position in the current market. Just like in 2008, I will only put it to work when the opportunities (due to pessimism in the market) are crystal clear again.

The market has changed

Passive investing has changed the markets. Whether this is a temporary phenomenon or a permanent change, we don’t know yet.

Does value investing no longer work as a result? Yes and no. Value investing will always work as long as there are human emotions on the stock market, and even passive investors have those emotions. But it might not be as easy as it used to be.

Although countless well-known investors have been doing it for years, I only truly saw the utility of a so-called ‘catalyst’ that can drive up prices in the recent period. In the past, it was enough for me to pay a fair price for a company and simply wait for the market to recognize the incorrect valuation. Rational valuation and patience were the most important factors; searching for a specific catalyst wasn’t necessary for me to achieve great returns.

Today, however, I see this as an essential factor. Take Somero Enterprises: great products, strong margins, good returns, hardly any debt, and cheap due to concerns about the construction sector. Our return so far? Only the dividend.

The price fluctuated significantly, allowing us to buy more at cheaper prices multiple times. Because of this, we aren’t suffering a loss, even though the price is currently below our initial purchase price. The stock simply remained cheap throughout the entire period.

I still believe in this company, but since we’ve had it in our portfolio for three years with almost no return, a significant price increase is needed to meet our target of a 15% compound annual return. Theoretically, this is still possible, provided the price moves toward the intrinsic value I calculated, within the next two years. That has happened more often in the past: first a long period sideways, then doubling in a few months.

Whether that will happen with Somero remains to be seen; we don’t have a crystal ball, after all. What we do see is that in the past year, three parties have built up a significant stake in the company. The price isn’t reacting to that yet, but it seems clear to me that these parties are up to something.

Suppose they take Somero private next year with a 50% premium. That would bring me to a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 10.7%. That’s not bad, but it’s below our 15% target. However, if I had only bought this year, when the catalyst became clear, that same takeover would yield a CAGR of between 22.5% and 50% (depending on the exact entry point and the timing of the bid).

This is a purely theoretical exercise since there is no bid yet, but it illustrates the difference between waiting a long time and realizing a profit in the short term. Where I previously rarely had to wait longer than three years for a stock to move toward its intrinsic value, we now have positions in the selection where we’ve been exercising patience for five years. The longer it takes, the lower the CAGR. In today’s market, dominated by passive investing, that catalyst has become crucial.

The question of why the price might rise, separate from a general market revaluation, has therefore become an essential part of my analyses rather than an afterthought.

You shouldn’t want to do everything yourself

Not trying to do everything yourself is another important lesson, perhaps not just from 2025, but over the entire 2022-2025 period. This applies in multiple areas, but I’ll limit myself to investing here.

I always wanted to come up with original ideas—stocks you hardly read about elsewhere. I spent hours searching with screeners and looked at a massive number of stocks, only to do nothing with them in 99.9% of cases. In the ‘cheap’ segment, the stocks were often cheap for a reason, or there were other factors that made them uninvestable to me. On the quality or growth side of the spectrum, the price was almost always the dealbreaker.

Driven by the urge to provide added value with original ideas, I lost sight of the essence: the goal is profit, not originality. You’ve probably already noticed this change in the last few issues; I’m now leaning more on my network and the ideas of others.

Of course, I continue to conduct the research myself. I sincerely couldn’t bring myself to outsource that. But copying stock ideas is one thing; truly handing over a portion is another. In our fund, a significant portion is now managed by others. Besides the protective options fund, these are other value investors who, like me, each have their own expertise and whom we know personally from conferences.

Actually, this isn’t entirely new, because holding companies have always filled that spot—I just didn’t see it that way before. Holdings are also essentially funds managed by others, each in their own way. The ‘stock in focus’ in this edition also falls under this.

I mentioned earlier that we are concentrating our portfolio more in a few ‘high-conviction’ stocks, as many of you find ideas elsewhere as well (and rightly so). Holdings can provide the necessary extra diversification here. Strategic rebalancing can further optimize their contribution.

Away from the craze of the day

My best moments are when I can just read and study the companies I encounter along the way. Getting away from the discussions about active vs. passive investing, or the battle between value, growth and quality. Actually, none of that matters.

Or rather: both quality and growth are simply part of the valuation. And because they are part of it, the valuation itself remains the most important thing. It’s about the price you pay and what you get in return; not whether a company grows 1% more or less than another, or whether the ROIC is a percentage point higher or lower. Everything is interconnected.

When you can work quietly, away from the craze of the day, all of that becomes much clearer. In that regard, the bi-weekly publication helps tremendously.

The advantages of retail investors

It’s often said that retail investors have big advantages over professional investors. Usually, people point to the larger pond to fish in, because as a retail investor, you can also invest in smaller companies. Or the pressure professionals feel to constantly beat a benchmark, while you don’t have that problem as a retail investor.

Both points are true, but in my experience of the past five years as a fund manager, this isn’t the biggest advantage. As a small fund, your fishing pond is still more than large enough, and if you have the right partners around you, that performance pressure isn’t too bad. Our partners in the fund share the same vision and show the necessary patience; I put more pressure on myself than they do.

The truly big advantage of a retail investor over a fund manager is control over the cash flows. As a retail investor, you know in advance what capital is coming in and what might be going out.

If you’re still working, you’re likely saving an amount every month. Are the markets at a peak? Then you can set that money aside and wait for a better moment. Are the markets in a slump? Then you can use that extra savings directly to pick up cheap stocks. Retirees also usually know in advance how much capital they need to withdraw from their investments annually, allowing them to plan.

A fund manager, on the other hand, has no control over that cash flow. Money flows in easily when the portfolio rises, at the moment when opportunities are actually smaller, and flows out when things don’t go as well as you would like. Exactly at the moment when it’s actually time to add more.

That control over the cash flow is a heavily underestimated advantage for the retail investor, and something I’ve learned to manage over the past few years. Of course, there are also advantages to being a fund manager, such as access to better tools and data, and shorter lines with both companies and other managers to exchange ideas.

Market Overview

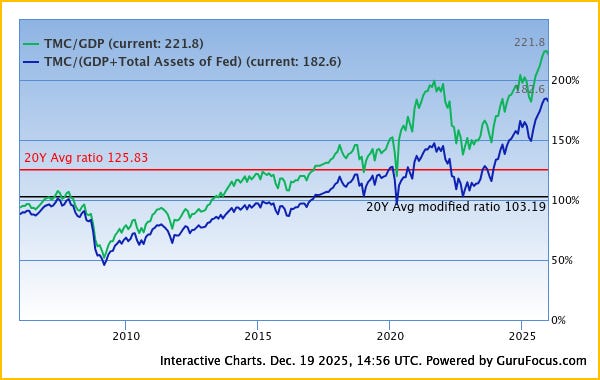

It’s been since late October that we looked at how expensive American markets are. The answer: even a bit more expensive than back then, at least according to the so-called Buffett indicator.

The ratio between total market capitalization and GDP in the United States has since risen to record highs above 220%.

Interestingly, the CNN Fear & Greed Index sat firmly in ‘Fear’ or even ‘Extreme Fear’ territory throughout this entire period. At first glance, that’s a tough one to square with an even more expensive stock market; usually, that kind of sentiment points toward a weakening market.

This raises an obvious question: how can these two indicators paint such a different picture? It’s actually quite simple: the CNN index focuses on a much shorter timeframe than the Buffett indicator. Both can be right at the same time, but as investors, we have to decide what matters most to us. For me, that’s always the long term.

Beyond that, we have to ask ourselves whether the indices—given the massive concentration in just a handful of stocks—still provide an accurate reflection of reality. How relevant are the price-to-earnings ratios of these indices when compared to their own historical averages?

There’s a bit of comfort in knowing that for us, as investors in individual businesses, all of this is largely secondary. What we do see, however, is that the expected future returns for investors buying these indices at current prices are steadily shrinking. They are settling for an expected return lower than what they could get today from government bonds. That isn’t rational investing; it’s simply hoping that the past few years will serve as a roadmap for the years to come.

But as Keynes (allegedly) put it: “Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

We’re sticking to our guns. Personally, I’m sleeping soundly, thanks to the protection provided by our cash position and the option fund.