VD 102: The Market and 100-Baggers

27/11/2025

In This Issue:

The Market and 100-Baggers

Stock in Focus: Engcon AB

The Rationality Test: Novo Nordisk

Doubler Portfolio Update

What I’ve Been Reading Lately

News from Our Companies

Thé Market and 100-Baggers

The Market

Why Should a Value Investor Care About the Market? You could rightly argue that the market doesn’t matter, because we don’t invest in the market, but in individual companies. Nevertheless, in recent years, the market has made things a lot tougher for us as active investors.

I’ve written countless times in the past about how passive investing is distorting the stock markets, and now, more and more academic studies are starting to point to the same conclusion. ETFs are a fantastic product and idea, but the hype surrounding them is currently overblown. Michael Green called it “the greatest story ever sold.”

My aim isn’t to rehash old arguments. Instead, I want to openly pose the question: “As active investors, should we have anticipated this shift in investor behaviour? And should it have prompted us to position ourselves differently?” The most crucial question is: what action should we take today?

It’s vital to constantly question yourself and your strategy. Not with the intention of jumping from one strategy to another—which, in my opinion, always means you’ll be too late. But rather to rationally assess whether your investments and portfolio have a bright future.

To answer the questions, perhaps we should have integrated the momentum factor more. However, positioning ourselves differently? No. My belief that price will ultimately follow value over the long term remains rock-solid. Taking action today? Absolutely not, that would truly be running behind the facts.

While the market doesn’t truly matter, it’s always useful as an investor to know what kind of market you’re operating in. Are you in a bull market (rising stocks) or a bear market (falling stocks)? This isn’t about the details, but the generalities:

How is the economy performing?

How is the stock market performing?

Are these two in alignment?

The motto here is: it’s better to be approximately right than precisely wrong.

And what do we do with this information? Not a whole lot, except when we see that the stock market is running far ahead of the economy, as is currently the case in the U.S. Or perhaps it’s the other way around this time: normally, the stock market leads the economy; today, we see the economy weakening, but the stock market isn’t showing it yet. Has the passive flow of money reversed this phenomenon?

The action we must take with this information is to be more critical of the stocks we select and also look for a catalyst that can drive the price up. A little extra cash wouldn’t hurt either.

Timing the Market vs. Assessing Value

Is this market timing? Yes and no. It’s primarily about weighing the market price against the market value. If stock prices are banking on a substantial increase in company profits, but the economy and results tell a different story, that’s not what we’re trying to time. Also, look at what Buffett did over the years: he also often partially stepped out when prices got too high, as he recently did with Apple. You could call him the best market timer of all time.

What I primarily want to highlight is that there’s a difference between trying to time the market based on gut feeling or charts, and looking at how value and price generally relate to each other across the board.

Look at the S&P 500, which has a Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio of 30. With flat earnings, that’s a return of 3.3%, less than you can get from a government bond. Where has the risk premium for stocks gone? You’re paying a (too) hefty price for uncertain future growth.

These are generalities, because we don’t invest in the market or the S&P 500—we select individual companies. Generalities are for the broader market, details are for our own companies.

The Pursuit of 100-Baggers

Another phenomenon typical of a bull market is constantly reading things where “the sky” is no longer the limit, but targets are apparently being aimed at the stratosphere.

Stocks that can go x10 and x100 are flying at us left and right. Investors are hunting for companies that can sustain an annual Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 20% or more for decades.

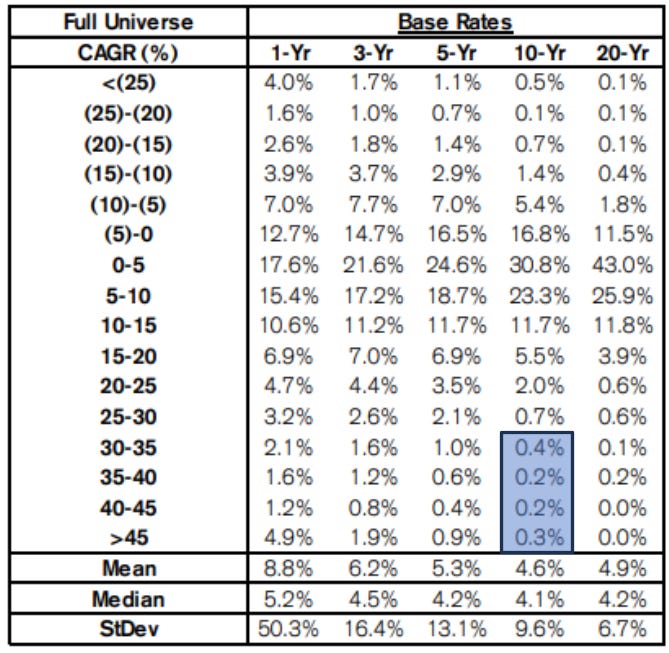

Let’s see if this is realistic. If we look at the base rates from Mauboussin, we see the following:

Companies that achieve more than 20% CAGR over 20 years are certainly not common. You’re looking at a 1.5% success rate. You might think you can increase those odds by being selective. Unfortunately, the companies that managed this kind of growth often didn’t look attractive based on their numbers at the time you should have bought them. You won’t pull them out of screeners.

Plus, they are often small companies when they start, which means you won’t easily discover them or even hear about them. Of course, after 20 years with those growth percentages, they’re no longer small.

There’s too much focus on the past. The Amazons of the world jump out at everyone. What gets forgotten is the very significant survivorship bias involved here. We all know the Amazons today; we don’t know the dozens of other companies that looked exactly like Amazon based on the numbers but failed to cross the finish line.

I get it. These investors are often still young and have plenty of years left to recover what they lose. Furthermore, if their gamble pays off, they hit a huge jackpot, both in terms of reputation and earnings. They’re often investing smaller amounts, and you need an x10 return to make a real impact on your life.

Chasing this with a small part of your portfolio is absolutely not wrong. A calculated gamble on something you genuinely believe in should be allowed. Just realize it remains a gamble, and adjust your position size accordingly.

I’m in a different situation. I’m now investing with a lot of money (at least, I consider it a lot). A lot of my own money, but also other people’s money. Like everyone, I invest to make a return. But most of all, I don’t want to lose money. If you hunt for stocks that go x10 or x100, you’ll also buy a lot of misses.

You shouldn’t risk what you already have and need for something you don’t have, and possibly don’t need. The very fact that we can invest means we’re already doing well. Ensuring we continue to do well is the priority, not pursuing unknown riches.

Look at it rationally: aim for companies that can double in five years. Even if we assume no change in valuations, roughly 15% of companies can achieve this through their growth alone. Moreover, these aren’t the obscure, small, unknown, high-risk, fast-growing companies; they’re often more stable companies whose value you can actually calculate. Add in companies that are still undervalued—where the return can come partly from growth and partly from a re-rating—and you potentially have 20% to 30% of companies to choose from.

Here, it’s also easier to separate the wheat from the chaff by avoiding loss-making companies and those with high debt. You can further increase your success rate.

Start by aiming for that x2, and who knows, maybe it will turn out to be one of those companies that can sustain that growth for 20 years. But do it step by step instead of chasing the dream of that one massive winner.