Lesson 10: Moats – The Foundation of Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Value investing 101

“A fantastic business has a wide, deep moat… filled with crocodiles.”

— Warren Buffett

One of the most powerful ideas in the world of value investing is that of the moat — literally: a moat around a castle. It’s a metaphor Buffett uses to describe companies with durable competitive advantages. Companies you can rely on for years. Companies that generate more value than their competitors — and continue to do so.

In this lesson, we take a deep dive into the concept of moats:

What exactly are they?

Why are they crucial for long-term returns?

What types of moats exist?

How can you recognize them — both qualitatively and quantitatively?

Why Moats?

A company with a strong moat can:

Generate above-average returns year after year;

Keep competitors at bay;

Grow without exhausting its capital base;

Recover faster from mistakes or external shocks.

In other words: a moat is your insurance policy against competition. Instead of asking “can this company keep winning?”, you know: this firm is playing a different game than the rest.

Without a moat, profitability is temporary. With a moat, profitability becomes sustainable.

As Charlie Munger put it succinctly:

“In the long run, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return—even if you originally bought it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result.”

What Makes a Moat Durable?

Two fundamental dimensions determine the strength of a moat:

The height of the return above the cost of capital

The duration over which that return can be sustained

It’s not just about how much value a company creates — but how long it can keep doing that.

The 4 Main Types of Moats

1. Strong Brand

A brand creates value when:

Customers are willing to pay more just for the brand;

The brand encourages repeat purchases (loyalty);

The brand is not easily replaceable.

Examples:

Coca-Cola (feeling of happiness)

Pampers (quality and trust)

Lotus (dominance in speculoos)

A well-known brand is not a moat if it doesn’t offer pricing power.

Renault is well-known, but gets no price premium. BMW does.

How to recognize it:

Higher prices than competitors

Consistent gross margin > 35%

Customer stays despite price increases

2. High Switching Costs

This is about locking in customers — not through contracts, but through friction.

Examples:

Software companies (ERP systems, accounting packages)

Banks (switching is a hassle)

B2B systems with deep integrations

Key characteristics:

Users invest time learning the system (learning curve)

Migration to an alternative is complex

The customer relationship is deeply embedded in the client's operations

Indicators:

Low customer churn

High margins and recurring revenue

3. Network Effects

The service becomes more valuable as more people use it. This creates a self-reinforcing ecosystem that is hard for newcomers to penetrate.

Examples:

Visa, Mastercard

Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp

Immoweb (more visitors → more listings → more visitors)

Networks often create a “winner takes most” dynamic. They scale quickly and deliver massive economic value.

How to recognize it:

Explosive growth among existing players

Difficult for newcomers to build a new network

Positive feedback loop

4. Low Cost Structure (Structural)

Not every low cost is a moat. Only structural cost advantages — those that are hard to replicate — offer durable protection.

Examples:

Colruyt (cost leader in Belgium)

Ryanair (ultra-low-cost model)

Coca-Cola (global distribution network)

Not a real moat:

Low-wage country production (easily copied)

Temporary scale advantages

Sustainably low costs:

Unique location or distribution chain

Network efficiency

Fully automated processes with high upfront barriers

How to Recognize a Moat in Practice?

1. Qualitative questions:

Can the company raise prices without losing customers?

Is there repeat use without the customer actively choosing again?

How hard is it for a newcomer to offer the same service?

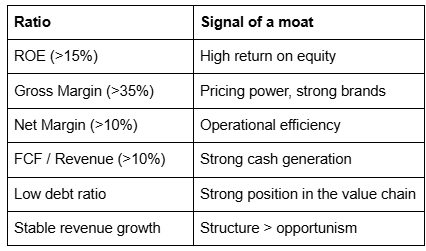

2. Quantitative signs:

Use financial ratios over a 10-year period:

📌 Always compare within the same sector!

Why Are Moats So Rare?

Because markets are competitive. High returns attract competition. Most companies lose their edge over time unless they actively invest in maintaining and strengthening their moat.

Technology, regulation, and changing consumer behavior can erode moats. Think of:

Newspapers losing ad revenue to Google

Nokia, Kodak, Blackberry — all once dominant

Airbnb shaking up the hotel industry

How Do Moats Stay Intact?

Use Porter’s Five Forces as a framework:

Rivalry among existing competitors

Threat of new entrants

Threat of substitutes

Bargaining power of buyers

Bargaining power of suppliers

Moats evolve. They grow or shrink. Regularly check whether your moat still holds.

Summary – Moat Checklist

Ask yourself these questions:

✅ Does the company have pricing power?

✅ Are there structural switching costs?

✅ Does the product/service become more valuable with more users?

✅ Does the company have lower costs that are hard to copy?

✅ Are margins and returns consistently high?

✅ Is the company relatively immune to new competition?

✅ Can I explain the competitive advantage in one sentence?

If you can answer ‘yes’ to several of these: you’ve probably found a moat.

Final Thoughts

Moats are the engines of value creation. Not every company has one, but if you learn to recognize them, you can dramatically improve your returns — and reduce mistakes.

The best part?

You don’t need to find them often.

As Buffett says:

“There are companies — you’ll find just a few in your lifetime — where any manager could raise returns just by raising prices. And they haven’t done it yet. They have an enormous source of pricing power they haven’t used. That’s the ultimate no-brainer.”

Value Investing 101: beginner friendly course

In the current market situation, I believe it's time to create an introductory series on value investing—a method that focuses on buying businesses at a price lower than their true value.

I like that you’ve clearly defined the quantitive aspects of a moat. Are the metrics mentioned, TTM or by 5/3yr average?