Is the hate for palm oil justified?

When a company operates in a hated sector, its stock price can remain low for a long time, and perhaps rightfully so. However, if the sector is hated but the reasons do not apply to the company, then it's a different story. Can such a company step out of the shadow of such a hated sector? Is the perception of the entire sector perhaps based on issues that are no longer prevalent or less common today?

I am referring to palm oil here. If we look at palm oil objectively, without emotion, we see how indispensable it is. According to the website palmoilscorecard.panda.org, a website of the WWF, palm oil accounts for 60% of all traded vegetable oils. It is present in 50% of all processed products such as frozen pizza, noodles, chocolate, personal care, and cleaning products. Additionally, 70% of all cosmetics contain palm oil components.

The WWF also indicates that palm oil is the most efficient to produce per hectare of land. According to the WWF, other vegetable oils yield 4 to 10 times less on the same land area. Furthermore, they generally use less water and fertilizers. In other words, perhaps palm oil should be viewed differently. And in that regard, I present to you one of, if not the, best company.

I introduce you to:

Sipef

Description

The 103-year-old company Sipef from Schoten, Belgium, engages in agro-industrial activities, primarily focused on palm oil and bananas. After selling its tea operations and a portion of its rubber plantations, Sipef now mainly focuses on these two products. The remaining rubber areas are being replanted with palm oil. There is also a small flower activity, but it has little impact on the figures.

Of these two activities, palm oil is by far the most important. In terms of planted area, bananas (and flowers) account for only 1.2% of the total, while palm oil or the rubber plantations being converted to palm oil make up the rest. In terms of region, we see that 82.1% of the hectares are located in Indonesia, 16.7% in Papua New Guinea (PNG), both for palm oil, and 1.2% in Ivory Coast for bananas.

With around 20 people, the company based in Schoten, Antwerp, manages around 22,000 individuals who are active in the aforementioned countries, alongside an administrative and trading office in Singapore.

In Ivory Coast, we find 5 plantations with 7 packaging stations. The bananas processed here are all Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade certified.

Sipef operates 36 oil palm plantations with 10 extraction factories, 7 of which are in Indonesia and 3 in PNG. 56% of the production in H1 2023 was realized in Indonesia, while 43.2% was produced in PNG.

About Palm Oil

When we talk about Sipef, we must discuss palm oil, both its positive and negative aspects, due to the fairly negative perception surrounding palm oil.

In an interview with VFB Magazine, CEO Francis van Hoydonck addressed this. A quote from this interview::

“The perception of palm oil prevailing in Europe today is based on figures and facts from five years ago. Today, the palm oil sector is the most regulated vegetable oil sector, with the most commitments from producers against deforestation, the development of peatlands, and labor exploitation.

The international study Forest 500, which has been tracking efforts and commitments to combat deforestation for 350 influential companies (including multinationals such as Unilever and Nestlé) and 150 financial institutions for eight years, confirms this. According to that study, we are a very good student, as we rank fourth on the list of 500 companies.

We are convinced that the negative perception surrounding palm oil will change fairly quickly, and the focus will shift to other crops such as soy in South America, cocoa, coffee, and rubber in Africa, or meat and timber production in several continents. These sectors have been much larger 'deforesters' than the palm oil sector in recent years. In 2021, deforestation in Indonesia reached its lowest level in over fifteen years.

In the meantime, we are already seeing a clear change in perception regarding palm oil in the food sector. Colruyt published a page on sustainable palm oil and how it contributes to the development of so-called emerging countries in its customer magazine. So, we are on the right track.”

If we objectively look at palm oil, without emotion, we see how indispensable it is. According to the website palmoilscorecard.panda.org, a website of the WWF, palm oil accounts for 60% of all traded vegetable oils. It is present in 50% of all processed products, such as frozen pizzas, noodles, chocolate, personal care products, and cleaning agents. It is also found in 70% of all cosmetics.

In Asia, palm oil is used for cooking, similar to how we use sunflower oil or olive oil. It is also present in animal feed, not to mention biofuels. Since the ingredients are labeled with more than 200 different names, it is also impossible for us as consumers to identify it in the ingredient list.

The reasons for the widespread use of palm oil are diverse. It is a creamy, uniform substance, making it ideal for mixing and processing. Additionally, it is odorless, colorless, and tasteless, allowing products to retain their original flavor. It is suitable for processing at high temperatures, and it contains a natural preservative that extends the shelf life of the products it is mixed with.

The above information all comes from the WWF, a nature organization, and is not promotional material from Sipef.

WWF also states that palm oil is the most efficient to produce per hectare of land. According to WWF, other vegetable oils yield 4 to 10 times less on the same land area.

Considering the land area for 1 ton of oil, we get this comparison::

If, on the other hand, we look at the production of the number of tons per hectare, we get the following comparison:

At Sipef, they speak of palm oil efficiency being 5 to 8 times higher than that of competing oils, and that palm oil accounts for a third of all vegetable oils. At WWF, they speak of traded oil, while Sipef simply speaks of all oil, but the difference seems quite significant, from 33% to 60%. However, palm oil is important for a wide range of products and sectors, not least to feed the world.

It is an efficient crop because it has the highest ratio of energy output to input. It requires the lowest input of pesticides, fertilizers, and fossil fuels per unit of oil produced.

Although the amount of land used is very important given that agriculture is the main driver of deforestation, I still want to emphasize that this is not the only important factor when it comes to the environment. For instance, sunflower oil has the least impact on water usage, which in my opinion is also very important to consider.

I always want to exercise caution with all studies produced on this topic, as it is not always clear who funded the studies, which often determines the study's perspective.

It is noteworthy that soy does not come out positively in any of the more recent studies (after 2017) compared to, for example, palm oil and sunflower oil, while palm oil was heavily criticized about five years ago. Deforestation and biodiversity loss were major issues then. What I found very strange at that time was that soy and livestock farming were not addressed simultaneously in this protest movement, even though both caused equal damage to nature. A cynic would point out that these latter two are very important for the United States.

RSPO

It cannot be denied that there has been, and still is, a problem with the palm oil sector. Often, the environment is sacrificed for profit, just like in many other sectors. An attempt by the industry to address this is the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO, which was established as early as 2004.

Initially, RSPO appeared to me as a lobbying group for the sector, but when you know that groups like WWF and other environmental organizations play a role in setting the standards for RSPO certification, which are also becoming increasingly stringent, the story changes.

Unfortunately, only 19% of palm oil producers are RSPO certified, the same percentage as in 2018. This is not a good sign, but it also indicates that the demand for palm oil is too high, and the rest can still easily sell their oil. It also shows that the conditions are not too lenient, as they are adjusted every five years.

There is also the Indonesian ISPO, which is a counterpart, but is it strict enough? For Indonesia, the palm oil sector is too important as an employer, which may make them too lenient. Approximately 40% of plantations in Indonesia are ISPO certified. The plantations of Sipef in Indonesia have both an ISPO and an RSPO label.

It is a wrong reaction from consumers and governments to ban palm oil. Products labeled "no palm oil" should prompt questions about which alternative is being used and what the environmental impact of that substitute is. Therefore, I believe that the EU ban on palm oil in biodiesel by 2030 is a wrong move; instead, all non-RSPO certified palm oil should be banned.

As mentioned earlier, it is almost impossible for consumers to check where palm oil is used, and it is also difficult to exert pressure on producers. For example, Kraft-Heinz conducted a campaign with products that are palm oil-free, but when you look at the WWF's Palm Oil Scorecard, Kraft turns out to have one of the worst scores in purchasing sustainable (RSPO) palm oil.

Nutella was strongly criticized for its use of palm oil, but Ferrero is actually one of the best-performing companies on the WWF list.

As consumers, we may have little impact, but as investors, we can make a difference. For instance, during general meetings, we can inquire about the use of palm oil and whether it is RSPO certified, or if they are aware of the situation with their suppliers. This is ESG in action, useful instead of mere talk in annual reports to reassure us. This question has already been raised during the meeting at Lotus Bakeries; Lotus also scores high on the list and is a very good performer.

Sipef is 100% RSPO certified. They aim for no deforestation, no exploitation, and no land grabbing. They also have 100% traceability; all production can be traced back to the field where it originates.

Sipef ranks ninth in the ranking of one hundred producers. Unfortunately, Sipef is just a small player, accounting for only about 2.5% of RSPO production and 0.48% of the total world production (2021).

Not directly related to RSPO certification, but equally important, are the social initiatives. Sipef also takes care of its employees locally.

Market position

As mentioned earlier, Sipef is just a small player, and we cannot speak of benefits in terms of scale or the like. One advantage of Sipef is that with its 100% RSPO certification, it can target the European market, where consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable products.

Sipef itself provides an interesting comparison with its competitors annually, and you can find the most recent one at:[https://www.sipef.com/media/2739/2022-peer-review-presentation.pdf]

Some interesting findings compared to some competitors:

The average age of planted hectares at Sipef is 9.8 years, making its areas the youngest in the overview compared to MP Evans. Personally, I find Socfinasia also an interesting player, where the average age is 12.3 years.

The advantage of a young age is that recent investments have been made and there is now a longer runway. The disadvantage is that oil palms only start bearing fruit after three years and full production occurs between the ninth and eighteenth year, after which the yield decreases again. An oil palm has an economic lifespan of about twenty-five years.

Sime Darby and Golden Agri-Resources are two of the largest players, with average ages of 12 and 16 years respectively. Sime Darby is not included in the table below because they do much more than just palm oil, making a comparison inaccurate.

Despite the relatively young age, we see that Sipef ranks fifth in terms of FFB (Fresh Fruit Bunches) per hectare, measured per ton. At Sipef, this is 22.1 tons, while Socfinasia performs slightly better with 22.2 tons. MP Evans scores higher with 23.2 tons, and United Plantations tops the list with 27.6 tons per hectare.

A second factor is the extraction ratio of fruit to crude palm oil. In this aspect, Sipef scores the best with 24%, while MP Evans also performs very well in third place with 22.9%. Socfinasia ranks second with 23.1%. Sime Darby and Golden Agri are noticeably less efficient with 21.1% and 21% respectively.

This results in a production of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) of 5.3 million tons per hectare for Sipef, placing it fourth. Socfinasia performs slightly worse with 5.12, while MP Evans slightly outperforms with 5.31. Golden Agri is at 4.26 and Sime Darby is at 3.51.

It is also noteworthy that Sipef achieves all this with very little debt, even compared to its competitors. Although there are some outliers, it cannot be generally said that others have a problematic level of debt.

None of these companies seem to be expensive. Socfinasia is slightly cheaper, while MP Evans performed slightly better and is therefore a bit more expensive. Also, the home bias plays a role, as we can follow Sipef much more easily. The headquarters are only a 17-minute drive from where I live.

Who

Our holding company, Ackermans & van Haaren, is the largest shareholder of Sipef, with a stake of 38.33% of the total. Luc Bertrand, former CEO of Ackermans and chairman at Ackermans, Deme, and CFE, as well as a board member at Bank Delen and Bank van Breda, is also the chairman of the board of directors of SIPEF.

The Bracht family collectively owns 12.32% of the shares through various entities. Sipef itself also owns 1.68% of the shares, bringing the total stake in the shareholder pact to 52.33%.

CEO Francis van Hoydonck has been active at Sipef since 1979 (longer than I have lived). From 1995 to 2007, he held the position of CFO, after which he became CEO.

Numbers

The returns of Sipef can be considered consistent over longer periods. However, in the short term, they fluctuate significantly due to the price of palm oil, which also determines the profit.

In the growth figures, we see some uncalculated numbers in the free cash flow. This is because the base was negative each time. All cash flow was used to invest in plantations, plantings, and replantings. Only now, with higher palm oil prices, is this cash flow positive.

It is important to note that when you start and end such a comparison, you can get very different figures. If you start in a period of high palm oil prices, the final year must also be very good to show growth figures.

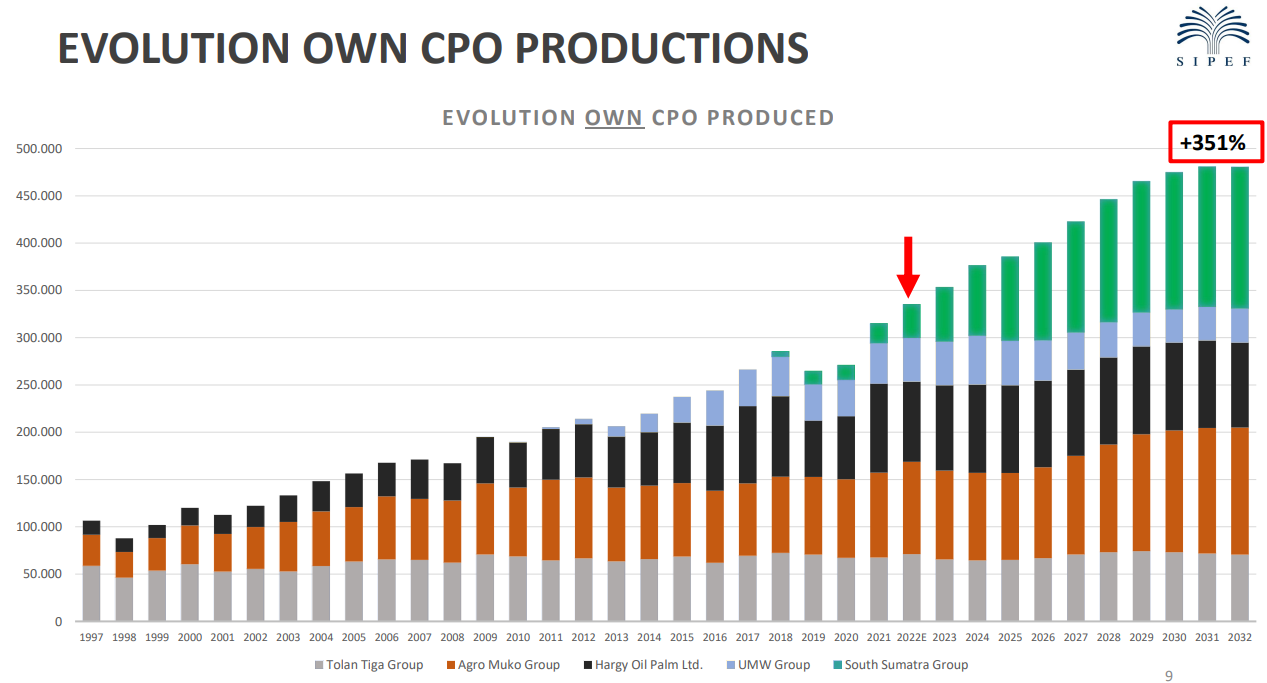

When we compare the fluctuations in revenue to the growth of the crude palm oil they produce, it becomes even clearer how significant a role the price of palm oil plays.

As you can see, the growth in CPO (Crude Palm Oil) production is fairly consistent. Of course, there are fluctuations due to weather conditions that may be more or less favorable. However, these are often offset by changes in price. In a period of low production, prices tend to be higher, potentially resulting in higher revenue.

However, the company only has control over the long-term growth of the plantations and production.

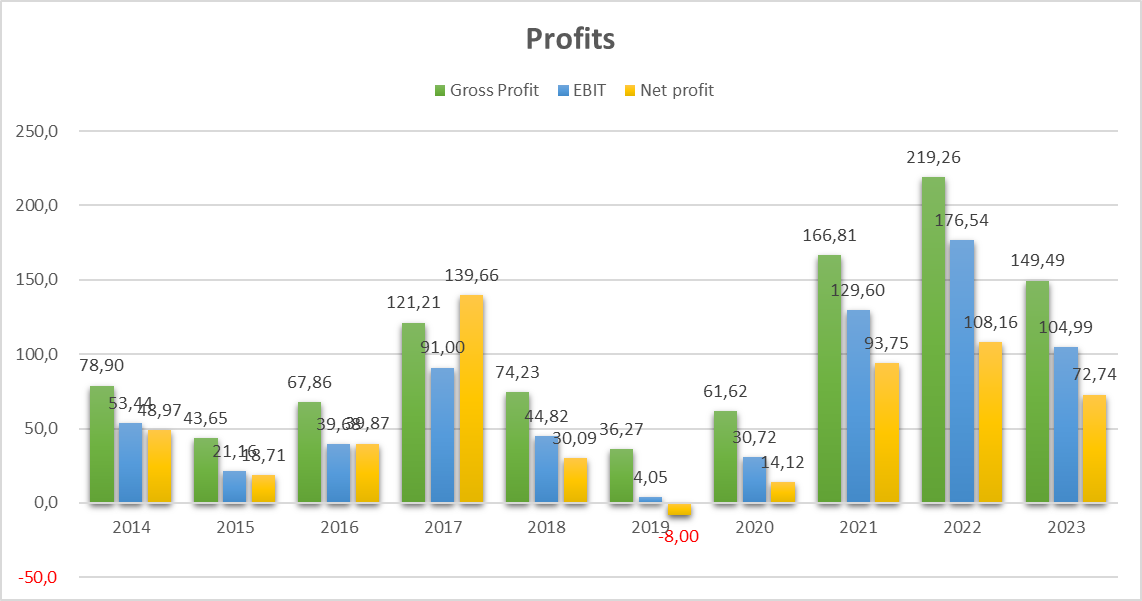

We observe a similar pattern in the margins, where they are relatively stable when measured over the long term but fluctuate significantly in the short term.

And as the revenue and margins fluctuate, we naturally see this reflected in the profit figures as well. In recent years, Sipef has received a good price for its palm oil, as we can see in the profit figures.

And also per share, we see the same movements. The growth of tangible book value might be the most reliable factor, although they also have to make write-downs on their plantations when the price of palm oil drops. They have to adjust this every year, which further affects the profit figures.

As mentioned earlier, Sipef does all this with very little debt. The figure below takes into account all types of debt. If we were to look at the traditional debt ratio, namely the interest-bearing debts minus the cash on the account, then Sipef would be debt-free.

Risks

The risk with Sipef is, of course, that we are dealing with a natural product and that a lot of things can go wrong with it, this happens regularly. Storms can destroy crops and even wash away bridges and roads. There have also been two volcanic eruptions. But it doesn't always have to be so extreme; fungal infections, prolonged droughts, or heavy rainfall all affect the harvest, sometimes even over multiple years.

In addition, the price of palm oil is crucial for the profit Sipef can achieve. Although Sipef is 100% RSPO certified, this does not provide any or hardly any price advantage. They also compete with other vegetable oils, such as soybean, rapeseed, and sunflower. External factors such as weather, which affect their harvests, also play a role in determining the price of palm oil. Traders and speculators who respond to all these factors and expand their inventory policy often exacerbate these fluctuations even further.

Furthermore, the biological assets (plantations) are also valued based on the price of palm oil, namely what they can generate in the future. This means that in times of high prices, an accounting profit is booked, and in bad times, there are additional write-downs, which increase the cyclical fluctuations.

Another risk, albeit smaller but still affecting profits, is that Sipef sells its products in dollars, while costs are incurred in the local currencies of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

Finally, there is also country risk. For example, Indonesia suddenly imposed additional export duties to support its biodiesel program. As a palm oil company, you just have to accept these duties. According to Van Hoydonck, however, this is a double-edged sword. With these duties, Indonesia pays for the blending of 30% palm oil into diesel; without them, demand for 9 million tons, accounting for 12% of global volume, would disappear. The question then is what hurts more for the received price: lower demand or the taxes to be paid.

Conclusion & Valuation

As mentioned earlier, Sipef seems to have no direct pricing power and cannot differentiate on volume due to its relatively small size. However, according to Van Hoydonck, there are still many efficiency improvements possible. For example, Sipef invests in better seeds with higher yields, which could become important in the future.

Additionally, Sipef assists small farmers in managing their land more efficiently. By focusing not only on themselves but also on surrounding farmers, Sipef seeks to differentiate itself by focusing on efficiency, which is also more sustainable.

The demand for palm oil is still growing at around 4% per year, mainly due to increasing consumption in India and China. I also consider the 100% RSPO certification as an advantage, as the demand for this is expected to continue increasing. On the other hand, many plantations may join RSPO, potentially diminishing this advantage. This remains to be seen.

Sipef plans to expand its planted area to 100,000 hectares by the end of 2025. This would double palm oil production in ten years. This expansion will be achieved through new plantings, replantings, maturation of existing plantations, and the conversion from rubber to palm trees. This allows Sipef to also benefit from the increasing demand.

However, it is important to note that Sipef is not alone in this expansion. The WWF predicts that palm oil production will increase by a factor of 4 to 6 between 2020 and 2050. The question is to what extent this will negatively impact the price of palm oil.

What about the price of palm oil?

The price of palm oil is virtually determinative of the profit Sipef can generate in any given year.

In the short term, there seem to be sufficient reasons to maintain a higher price. There is a strong demand for all vegetable oils, and palm oil remains the preferred oil in regions where the population is still growing, such as Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and South America.

Moreover, the supply is rather limited due to the restricted availability of agricultural land. Expansions are hindered by governments and environmental activists.

Additionally, the price was very low between 2018 and 2020, leading to a lack of fertilization and insufficient replanting. As there were not enough old trees replaced in the sector, the current plantations are less profitable than five years ago. However, Sipef continued to invest more in this aspect.

This pattern seems to be reversing now, as prices have remained high over the past three years, leading to increased investments in the sector. We may already see this effect this year.

Zooming out and looking at the past 20 years, we can realistically expect a price between $800 and $1000 for the next five to ten years. Of course, the price will follow inflation, so if inflation remains strong, it could be higher. Therefore, in valuations, it seems safe to assume $900 per ton.

Valuation

Valuing companies dependent on highly fluctuating prices, such as Sipef with palm oil, can indeed be challenging. Methods like discounted cash flow or price-to-earnings ratios may be misleading because they tend to extrapolate recent history too strongly. A low price-to-earnings ratio could indicate a company at the top of its cycle and actually expensive, while a high price-to-earnings ratio could indicate a company nearing the bottom of its cycle and actually cheap.

Comparing companies in the same sector can also be misleading because they are likely all expensive or cheap together, given they are in the same business.

If you still proceed with a valuation based on the discounted cash flow method, you arrive at a wide range of €70 to €145 as a possible fair value. It makes little sense to specify the growth applied to this, as everything depends on your assessment of the palm oil price for the coming years. If you are wrong about that, then the rest of the analysis would also be incorrect.

Even the reproduction value, which amounts to €80 and which I also consider fair value, depends on the valuation of the biological assets and therefore on the palm oil price.

The belief in the commodity, in this case, palm oil, is crucial when evaluating companies like Sipef. The key is to find the best company operating in this commodity, not necessarily the cheapest.

Here is the graph illustrating my belief in palm oil as a commodity.:

An increasing demand for vegetable oils for food, animal feed, and biofuels is accompanied by a decreasing amount of agricultural land per person, mainly due to rising population.

The growing demand for food is not only due to population growth but also to improved living standards in many emerging markets. People there now have more disposable income and are consuming far below the levels of Europe or America.