Are you assessing value or assigning a price?

The Dotcom bubble and subsequent crash kept an entire generation of people away from the stock market. Many believed in the late '90s of the previous century that the stock market could only go up. I was a new investor at that time as well, but fortunately, I was pushed in the right direction.

Many started investing, and made fantastic profits in a short period, only to lose everything later during the crash. It doesn't seem as bad to me today. The companies that are currently making a lot of noise are solidly profitable; they are just too expensive. This seems more like the nifty-fifty period of the late 1960s and early '70s. But that can also deter an entire generation from the stock market because nobody wants to look at losses for more than 10 years.

Like during the nifty-fifty period, today we see significant differences in the market, ranging from very expensive companies that are getting even more expensive to cheap companies that, at best, don't move in price.

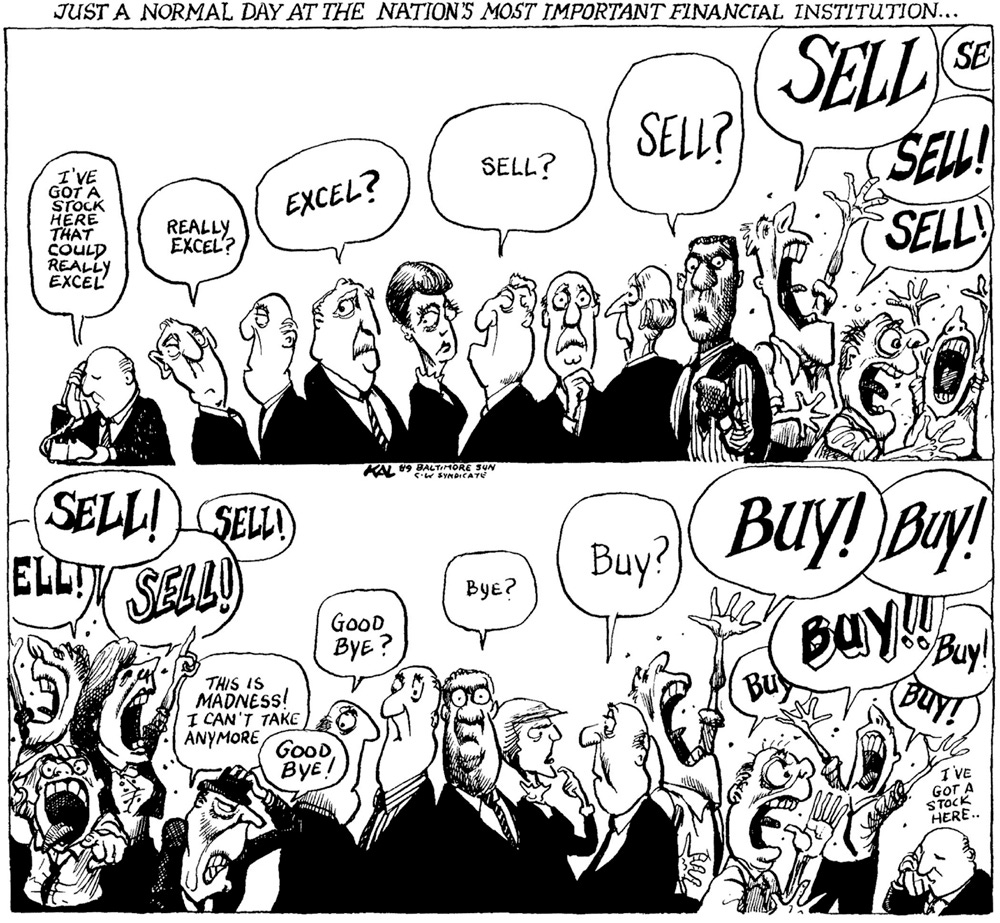

I think that's because, in periods like the nifty-fifty, the Dotcom bubble, and even today, stocks are no longer valued but are given a price. I partly borrow this explanation from Professor Aswath Damodaran. (Watch a great Google Talk with him).

What is the difference between valuing and pricing?

What is the difference between valuing an investment, primarily companies in our case, and simply assigning a price to it?

The value of an investment, in simple terms, is what it can yield for us in the future. I will go into more depth shortly on what we need to do before we can calculate this, but first, let's take a look at determining a price.

Pricing is something we all do, but it becomes clear with the help of an example from a real estate agent. How does a real estate agent determine the price of a house or apartment they are going to sell? They search for comparable properties in the area and look at the prices at which these are listed and have been sold. Because the real estate market is so extensive, they can easily find several properties that are relatively comparable in terms of size, age, condition, and so on. Additionally, they also take into account differences, such as the number of bedrooms and the quality of the finishing.

In this case, they haven't conducted a valuation of the property but have arrived at a price that corresponds to what is currently being paid for short-term buying or selling.

As I mentioned before, this is not a valuation but rather a way to align supply and demand.

Supply and demand

Likewise, on the stock market, the price formation of stocks is a game of supply and demand. This also means that the price of a stock may not have anything to do with the value of the company.

Is it therefore meaningful to value a company? Or would it be better, just like in the real estate market, to price stocks on the stock market?

And actually, the latter is what I see happening very often today, often even by people who think they are practicing value investing. Instead of valuing a company, they look for comparable companies and see how they are priced. For example, if the comparable companies have an average price-earnings ratio of 16 and the company they are looking at is only at 10, then the conclusion is that this company is 37.5% cheaper than the rest.

This is, of course, a quick way to assign a price to something, and it seems to work today. It has become a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy because so many people are doing it.

If you apply this approach, you are essentially assuming that the stock market is generally efficient and accurately determines the price of stocks, but that occasional errors creep in. The cheaper company is seen as a mistake that the market will quickly recognize and correct to the right price.

But have you actually bought something below its value? It's possible, but it could also be that the companies you are comparing to are overpriced.

Furthermore, no two companies are exactly comparable. The markets they serve differ, growth prospects don't match, access to capital can be different, debts vary, and so on. There are too many factors in which companies differ compared to apartments to apply the same strategy, or at least that's my opinion.

The question I also ask myself in this context is whether you are investing in companies at that moment or trading them.

Investing or trading

I still view a stock as a piece of ownership of a company. For me, the value of the company can be directly translated into the value of a share in that company. In short, I want to invest in companies, not trade stocks. And I must admit that over the past two to three years - sometimes frustratingly - I have had to watch trading strategies yield more than investing in companies.

However, I am 100% convinced that, just as in the past, the price of stocks will always return to the value of the company, both positively and negatively.

So when I buy a stock, I conduct a valuation of the company to ensure that I am getting a bargain or paying the right price for an excellent company. Because even the best company can be a bad investment if you buy it too expensively.

Valuation

If you want to determine the value of an apartment or house instead of the price, then you need to assess what this property can yield for you in the future.

You need to estimate what the rental price will be in the coming years, how many expenses you will have, potential vacancies or non-payment, the cost of capital (loan and equity contribution), and then determine a final selling value.

All of these aspects involve assumptions. Let's start with the rental price. How will it evolve? Will it increase due to population growth? Is the neighborhood where the property is located becoming more popular? Or perhaps not. Maybe many properties in the area have become outdated and dilapidated, which could lead to less demand for rental apartments in that neighborhood.

Expenses are also not always easy to estimate in the short term, but in the long term, you can account for a certain degree of wear and tear, replacement costs, and so on.

The level of vacancy will again depend on the neighborhood's development, but non-payment is not always predictable. Tenants may lose their jobs or get involved in accidents, and so on.

You also need to consider the cost of the capital you are investing. The part you are going to borrow is easy, those are the interest costs you pay, and this even creates a leverage effect. But for your own equity contribution, you also need to calculate what it could potentially earn elsewhere (preferably risk-free). Today, that's around 3%, but it hasn't always been the case. Not too long ago, for example, it was 0%, but it has also been 6% or even higher at times. How do you expect this to evolve? Also, be sure to consider purchase costs such as registration fees.

The ultimate selling price will also depend on several assumptions, like those related to rent, but also the costs to build a comparable apartment anew.

In short, to determine the value of an apartment, you have to make a large number of future estimates, some of which may or may not come true. Some expectations may be too low, while others might be too high.

And that's still nothing compared to what you have to do for a company. For companies, all these assumptions can become even more complex. But it's precisely the process of determining all this data and estimates that helps you better understand the company, the sectors it operates in, the management, and so on.

For all these estimates, you can always obtain a pessimistic, realistic, and optimistic figure, giving you a range of what the company may be worth instead of just a single number.

However, I often work with just one figure because it's simpler to communicate. This then forms an additional assessment of the probability you assign to each scenario.

In summary, if you want to invest for the long term, value your investments. On the other hand, if you are more focused on the short term, learn to "price" stocks.