0.3 x tangible bookvalue? Too cheap

Today, I’m introducing you to a company that has been growing its tangible book value for 30 years, the last ten at 9.5% CAGR, yet is currently trading at just 0.3 times this value.

You might immediately think something must be seriously wrong with the company, but that’s not the case. It’s a highly cyclical business that, after a massive peak, has had a poor 2023 and was unprofitable.

However, several long-term trends support the company. For example, the growing global population needs to be fed, while available farmland is becoming increasingly scarce.

The company is also not at risk of bankruptcy. With a debt ratio of only 9% – or, alternatively, 1.4 times the weak EBITDA of the past twelve months – there’s no need for concern.

An investment thesis doesn’t have to be complicated.

Let me introduce you to:

K+S

Description

The German company K+S manufactures potassium and salt, which explains the name Kali + Salz.

Founded in the mid-19th century, the company has mining and production sites in Europe and North America. K+S operates globally and has sales points on all five continents.

The Werra mine in Germany and the Bethune mine in Canada are the two main locations for extracting these raw materials. Additionally, there are other salt mines; salt is partly mined and partly extracted from saltwater.

The products resulting from these mining activities, whether produced by K+S itself or by their customers, are used in chemicals, industry, food processing, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, water treatment, and de-icing salt. For those interested, K+S has created a short video about these applications.

However, our focus remains on the fertilizers they produce from potassium and salt. Potassium, along with nitrogen and phosphorus, is an essential component for plants. Potassium makes plants more resistant to extreme weather conditions and increases the efficiency of water use by crops.

In addition to the usual fertilizers, very specific applications have also been developed to meet particular needs, including those of organic farming.

The company was previously part of Smart Capital's portfolio (The Dutch version of Valuing Dutcham). Those who were subscribers at the time may recall the ongoing misfortune faced by the company.

First, there was the drought in 2018, which impaired the optimal functioning of the Werra mines. The drought prevented the disposal of wastewater. Additionally, environmental standards in Germany became much stricter, making the situation even more challenging.

In 2019, extremely low prices for agricultural products followed, leading farmers to cut back on spending and purchase fewer fertilizers. This was further exacerbated by the import ban on potassium from China.

All this occurred while the Bethune mine in Canada was still in the startup phase, incurring significant costs. Debt levels increased, prompting K+S to divest its salt division in America.

Following these measures and restructuring, the debt has been significantly reduced. In 2022, the company experienced a period of strong profitability because, due to the war in Ukraine, two of the three largest potash mines were no longer allowed to supply their products to America and Europe. In short, debt is no longer a concern.

Nevertheless, the company must continue to work on optimizing its existing business, with a specific focus on potassium and magnesium to address the megatrends of food, water treatment, and energy. Given the changing climate conditions and the growth of the global population, K+S's products are essential for feeding the world.

Additionally, K+S is constantly seeking ways to better utilize its existing infrastructure and repurpose it for other uses. For example, a joint venture in waste management has been initiated, and research is underway to explore whether captured CO² can be stored in their mines.

Market position

K+S is the largest salt producer in Europe, ahead of Salins, Artuomsol, Nouryon, and Südsalz. In terms of potassium, K+S ranks fifth with a production of about 7 million tons, following Nutrien (20 million tons), Belaruskali (13 million tons), Uralkali (12 million tons), and Mosaic (10 million tons), and just ahead of ICL, which produces 5 million tons.

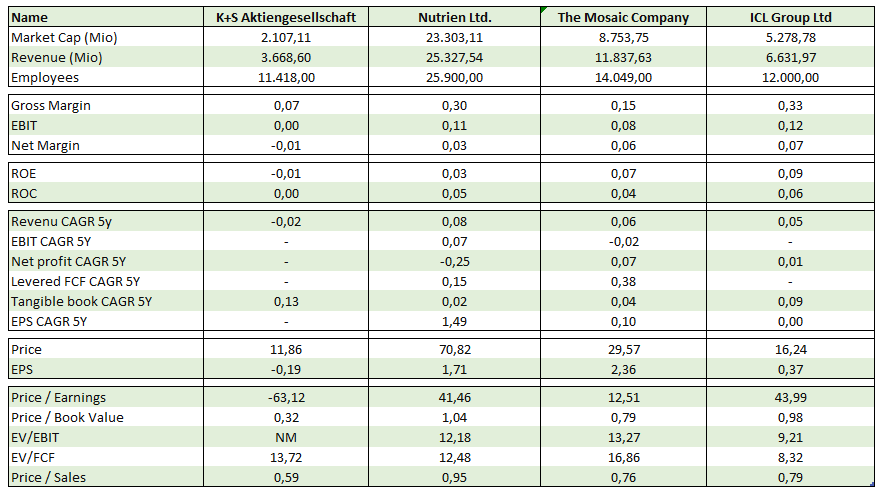

In the overview below, I compare K+S with its Western competitors. Information on Belaruskali has not been available since 2021, and Uralkali has been delisted from the stock exchange since 2019.

Unfortunately, the comparison is not entirely accurate. For Nutrien, the contribution of potassium is only 13.4% of revenue, for Mosaic it is 27.2%, and for ICL it is 29%. The rest of the revenue comes from other products and applications. At K+S, potassium likely accounts for around 70% of revenue. Unfortunately, they no longer report this revenue separately, instead differentiating between "Agriculture" and "Industry + Consumer." Although a significant portion of the revenue in the "Agriculture" category is likely potassium, the distribution within "Industry + Consumer" remains unclear.

Nevertheless, from the comparison, we can conclude that K+S has significantly underperformed compared to its competitors over the past twelve reported months (up to March 31, 2024).

This is primarily due to the period from April 1 to September 30 of last year. During those two quarters, K+S reported a loss. Although competitors also experienced a strong dip in potash prices during this period, only Mosaic reported a loss.

The lower potash prices during this period were further impacted by strikes at the ports of British Columbia in Canada. Mosaic and K+S were more affected by these strikes than the other companies.

The bottom of the potash prices was reached when Mosaic and Nutrien, through their export alliance Canpotex, sold potash to China for $307 per ton. This happened despite the fact that China also has its own production and imports potash from Russia and Belarus.

In my opinion, the strike at the port cannot be the only reason for this poor performance. The annual and quarterly reports also reference rising costs for energy, labor, and raw materials.

Although having mines on two continents would normally be an advantage, this was clearly not the case last year. Although not specifically stated, I believe that the increased costs primarily originated in Europe. Unit costs have since decreased. In short, we are now at the worst possible comparison point; with the presentation of the half-year figures in mid-August, an improvement is expected.

The slowing market in Brazil was also specifically mentioned during that period, which typically came from the German division.

Who

K+S does not have strategic shareholders who are actively involved in steering the company. In other words, it seems that the leadership at K+S consists of a group of managers who prioritize job security over the well-being of the company itself. Although the interests of the company often align with strategy and job preservation, we must recognize that their salaries are more important to them than the company’s performance.

Why do I write this so sharply? In 2020, they sold the salt division in America to reduce debt. This was not an unusual move given the weak results and the need for debt relief. They could have anticipated this a year earlier, but the sale occurred after an exceptionally mild winter in America, which resulted in minimal sales of de-icing salt and weak figures.

Furthermore, they continued to pay dividends during those two years. If you sell part of your business to reduce debt, it would make sense to also cut the dividend. The failure to do so can be attributed to the resistance from some funds, which explains the decision. This indicates a priority for job preservation over the company's interests, which was also the reason for my decision to sell in 2020.

Today, the same Chairman of the Board, Andreas Kreimeyer, and the same CEO, Berkhard Lohr, are still in place. CFO Christian Meyer and COO Carine-Martina Trözsch have been newly appointed to the executive committee since last year. Christina Daske, who has been with K+S since 2012 and outlined the new strategy after the sale of the salt division in America, is also part of the executive team as HR Director.

Numbers

Due to the losses in the second and third quarters of last year, we cannot derive much benefit from the above growth figures. After all, there is no growth with a negative number. However, in our investment thesis, tangible book value is of utmost importance, and over a period of ten years, including the difficult periods, we still see a compounded annual growth rate of 9.5%.

We also observe that margins and returns are certainly not at their peak; quite the opposite. We know that we are not at the top of the cycle but rather close to the bottom.

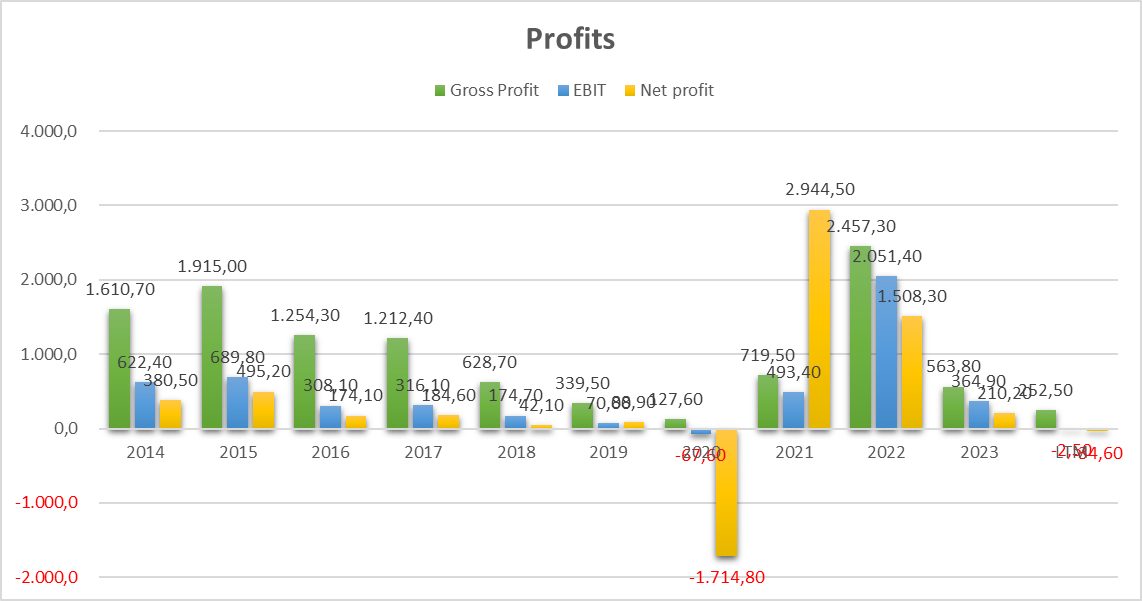

Without the commissioning of the Bethune mine in Canada in 2017, the revenue in 2018 would have been significantly lower. However, the two years following that were even more challenging. In this table, we can also clearly see how exceptional 2022 was.

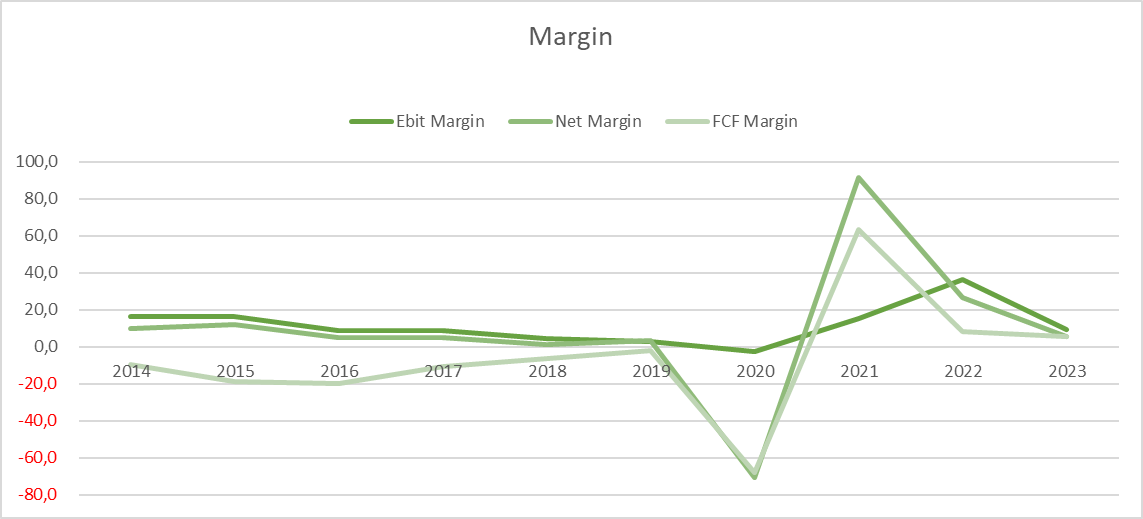

This margin table is distorted by a significant write-down in 2020, which was reversed in 2021. This explains the two enormous peaks, which make the rest of the chart less readable. The only line we need to closely monitor is that of the operating margin. Here too, we see that it was much lower during the period from 2018 to 2020, followed by an exceptional peak in 2022. Today, we are also below the average.

The same conclusions for net income are evident in these figures as with the margins. Operating profit also shows the weak years and the huge peak in 2022.

For a cyclical and capital-intensive company, tangible book value is a good measure to determine where you are in the cycle. If the company appears cheap based on earnings but is expensive compared to its own historical tangible book value, you know you are at or near the top of the cycle. However, if the company seems extremely expensive based on price-to-earnings ratio or EV/EBIT, or is even making a loss, but is very cheap relative to its tangible book value, then you are likely close to the bottom of the cycle.

In the overview above, the rising debt relative to equity is visible until 2020. The reason for this was the construction and expansion of the Bethune mine. It was clear that action needed to be taken. The result of that action is also evident in the subsequent years.

Risks

K+S is not a high-quality company. If the comparison with competitors hasn’t convinced you, then the lack of an engaged shareholder and the current management are certainly decisive factors for me. However, this doesn’t necessarily have to be a problem; mediocre companies can still be good investments if they are cheap enough. What we need to do is keep a close watch on the risks.

One of those risks for me is the company’s leadership, as mentioned earlier. Their ambition to achieve an average return on capital (WACC) over a period of five years is rather modest and doesn’t provide a strong motivation to invest in K+S in the long term. As an investor, you want to earn more than the cost of capital.

The sale of the salt business in America after a very weak winter, rather than the year before, also reflects a lack of vision. The costs of the Bethune mine were clear, and they could have acted more quickly following the drought and the Chinese import ban. The fact that the dividend was not cut is, for me, the best evidence of poor capital allocation skills.

K+S is also a very cyclical company that depends on many external factors beyond its control. Weather is a significant factor, not anymore for production—since they are now equipped to handle droughts in the Werra mine—but for the sale of fertilizers. Farmers are dependent on the weather. The price K+S can receive for its potash and finished products is crucial and can make or break a year with the same volumes.

In weaker periods, they even fail to cover the cost of the capital used.

This introduces enormous volatility in the stock price, and as investors, we must withstand this volatility.

Additionally, there are environmental risks. While K+S operates with high standards, it is uncertain how this regulation will evolve in Germany and Canada, and whether they will be allowed to operate in the same way. The saline wastewater left over from potash mining must be processed properly. Previously, this was reinjected, but that method and river discharge have been severely restricted. Nowadays, it is stored, and these storage sites are being restructured so that the natural processes can handle it. This is a more expensive and slower process.

Conclusion & valuation

From the above, you can already infer that there is only one reason why I am buying the company: because it is very cheap and we are near the bottom of the cycle, although unfortunately, we do not know how long this will last.

However, there are also some long-term arguments for the entire sector. There is increasingly less agricultural land available while the number of people to be fed is rising. Therefore, production per hectare must be increased, which means a greater demand for fertilizers.

Additionally, their products are used for water treatment. While water is abundant, potable water is scarce.

Plants also need to become more resistant, and potassium plays a crucial role in increasing resistance.

Currently, the demand for potassium is higher than the supply. BHP is developing a mine, the Jansen Project in Saskatchewan, Canada. The first phase of this project, which is expected to be operational by 2026, will be the largest mine in the world with a capacity of 8.5 million tons. By 2032, the second phase will be completed. The total cost of this project is estimated at $10.5 billion.

K+S will also be adding extra capacity to the Bethune mine in Canada, potentially bringing this mine into the top 20% of the most efficient producers.

From the BHP project and K+S’s Bethune mine, we know that developing a new mine is a very lengthy and costly process.

The demand for potassium is steadily growing by 2-3% per year. It is expected that by 2032 there will still be a shortage of about 4 million tons per year.

Despite these positive factors and the ability to conduct valuations with normalized assumptions, I will keep it simple. Note that various valuations, depending on negative to positive scenarios, range between €20 and €58, but I won’t use these.

I keep it much simpler in this case. K+S is currently trading at 0.3 times its tangible book value. This tangible book value has grown nicely in the past and has only sporadically declined over the past 30 years. Such declines often occurred after an exceptional increase, followed by a brief dip, after which the upward trend resumed.

After the setback in 2020, we have also seen two significant increases; another setback is therefore not out of the question. However, this would likely result from a write-down of the mines. For now, I see no signals pointing to that, but I am keeping it in mind.

If we return to the tangible book value of 2019, before the sale of the salt division in America and with the high debt, there would still be an upward potential of 50% compared to the current share price.

If we revert to the €27.06 per share tangible book value of 2021, this presents an upside potential of 128.7%.

Both scenarios also consider a valuation equal to the tangible book value. In the past 30 years, there has been only one year in which K+S did not trade above 1x tangible book value during the year, and that was last year. On average, K+S has traded at 1.08x tangible book value over the past ten years, with peaks of 2.28x and lows of 0.28x.

For safety, I set the fair value around €30, which is below the tangible book value of €35.36, to account for a potential decline.

As mentioned, K+S is close to the bottom of a cycle and is incredibly cheap. The company has a solid balance sheet and faces both positive and negative factors in its sector, with long-term benefits outweighing the negatives. We accept the risks of additional environmental regulations and management issues at this price.